An Attempt At Exhausting A Place In GTA Online, Michael Crowe, 2017

essay

What Do You Want Michael?

Originally published as the introduction to An Attempt At Exhausting A Place In GTA Online by Michael Crowe

Available to buy from Studio Operative

If you asked me to summarise the plot of Grand Theft Auto V, the multi-million dollar grossing video game developed by Rockstar in 2013, I’d probably go for something glib, like this: It’s a story about a man named Michael experiencing a mid-life crisis. That seems like a useful description to keep in mind whilst thinking about this introduction too, because if you asked me to summarise the contents of the book you now hold, I’d be tempted to say something very similar. While our author Michael Crowe may not be facing the tripartite tribulations of Grand Theft Auto’s Michael De Santa (…an adulterous partner, the lucrative call of the criminal lifestyle, and the kind of psychiatric instability that only $$$s worth of top-tier therapy is likely to cure…) he’s evidently experiencing a very real crisis of his own. It’s a crisis that arises directly from spending prolonged periods of time in a virtual environment whose liquid sunsets, infinite highways and piquant dialogue have been perfectly calibrated to make him drool. From within this sublimely rendered amniotic sack, he’s been pretty well positioned to observe what kinds of things might happen to us when we enter the locales of communal game worlds, what forms of time we’re likely to experience whilst we’re there, and what kinds of epiphany we might encounter as a result.

But Kifflom be praised! So much has happened in the world of video games since the release of GTA V, and the game continues to top charts as one of the most popular pieces of recreational software available. If, like me, you’ve had the time-draining misfortune of playing the franchise through its fifteen iterations, across four generations of consoles and multiple platforms, you’ll be fully aware of its perennial appeal. It’s an allure that oscillates between an ability to support both immersive story-driven campaign play and a compelling sandbox experience that saps maximum life hours through near-limitless, non-goal-oriented, meandering exploration and sadistic hi-jinx.

Unlike other expansive ‘next generation’ open world games in which a sense of threat is always palpable - think CD Projekt Red’s The Witcher 3 or Bethesda’s magisterial Skyrim for example - Grand Theft Auto V’s default experience is enticingly ambient: there’s a seemingly unlimited appeal in being left to one’s own devices in a sunbathed pseudo-Californian state saturated with vice and corruption. Casually spawning at the door of a safe house, the forecourt of a hospital or the commonly bloodstained steps of an LSPD police station, players are presented with a challenging but initially benign and indifferent world to exploit. Pedestrians pass, muttering into their cellular phones, vehicles cruise by frequently, pumping the beats of Radio Los Santos or the humorous natter of West Coast Talk onto the street. The magnitude of this world is awe-inspiring. Indeed, its secrets are still being exposed years after players were first given the opportunity to explore its vast oceans, scorched deserts, industrial hinterlands, backwater towns and mysterious mountain tops. That the multiplayer component of the game, GTA Online, has allowed players to work independently or co-operatively to manipulate the world’s possibilities only continues to further the exponentially limitless sense of its replay value, prolonging its oceanic attraction.

Now, rather terrifyingly, so much has also happened in the real world of global politics since the small book you now hold was written, that the hallmark satire of the GTA series no longer reads like a caustic send-up of American excess, but a prescient diagnosis of U.S. psychopathological mania. The game might provide a comforting homeliness - tolerated as it is by households across the world - but what should really ring a few alarm bells right now is how little difference we can draw between its comedic deconstruction of U.S. politics and the contemporary shit storm we’re experiencing post-Trump. The game world no longer offers a refuge from reality, drawn at a critically lucid distance, but seems to perfectly mirror reality’s free-fall into chaos.

That ‘The Donald’ replicates the uninhibited brashness of Rockstar’s parodic politicos is something I’m less inclined to read as a validation of the franchise’s foresight, more as an indication of the intimate relationship video games and the communities that they establish and sustain have with the political world beyond the virtual domain of play. Take Jock Cranley for example, GTA V’s conservative candidate in the San Andreas State gubernatorial election. Cranley is an ex-TV star whose professional detour onto the campaign trail evinces a supposedly virtuous attempt to redress the balance of power from an aloof political elite whilst fighting hard for the ‘underdog’: that ‘white, god fearing heterosexual this country now hates’. This single line of spoof rhetoric perfectly encapsulates the guiding sentiments of contemporary populist indignation in the United States, and especially the emergent youthful milieu of the ‘alt-right’, an amorphous body whose politics are slanderous, anti-‘SJW’, offensively right-wing, but ultimately fugitive, unknowable in both their real world embodiments and sincerity.

It’s no surprise that video games - still a contentious medium in their own right, now proving to be a more popular past-time than cinema - regularly cross over into the political domain (…heck, in the UK we even had the worm-tongued Labour MP Tom Watson defending the brilliance of the GTA franchise against intrusion from moralistically blinkered politicians in The New Statesman…). Grand Theft Auto and other titles produced by Rock Star, notably Manhunt (2003), have brought the studio under sustained media and legal scrutiny due to supposed ‘copycat’ incidents. While research into the aptitude of video games to affect our behaviour is still wholly inconclusive, the case of Devin Darnell Thompson - an Alabama man who, after being arrested on charges of ‘grand theft auto’, uttered the words ‘life is a video game, you’ve got to die sometime’ before proceeding to murder three police officers - certainly complicated matters for Rock Star when prosecutors absurdly claimed that they had prewritten the crime in a mission included in 2002’s Grand Theft Auto: Vice City.

But more interestingly for the purposes of this essay perhaps, is the ‘Hot Coffee’ debacle occurring a few years later, in which traces of code were mysteriously left within purchasable copies of Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas (2004), allowing players to modify the game to simulate explicit sex acts. Despite costing the game’s publisher, Take Two, a near $20 million dollars in damages, the case highlighted the compellingly clandestine relationships, private languages and bonds of trust with which game developers are keen to engage their fans, suggesting that gaming communities embodied a kind of ‘shadow populace’ entirely capable of producing their own codes of conduct (or ‘codes of honor’ as the artist Jon Rafman might put it) beyond those defined by the legislative protocols of a sovereign state.

Both of these cases are emblematic of the enmeshment of virtual worlds and the freedoms they promise with the strictures of legal infrastructure and societal constraint in real life, a porous relationship we’d better start getting used to given the implications. In his 2007 book Gamer Theory, McKenzie Wark coined the phrase ‘military-entertainment complex’, a useful term that allows us to address the intricate interrelationship of the game industry with dubious practices of martial subject-formation. Think for example of U.S. Air Force drone pilot recruitment drives taking place at competitive gaming conventions, chillingly documented in Tonje Hessen Schei’s documentary Drone (2014). Or developer Ubisoft’s widely contested but continued production of America’s Army (2005), a military simulation in which players are given the opportunity to sign up for a career in the United States Army from an in-game menu. Think also of the preliminary actions of ultra-right wing terrorist Anders Breivik, whose mass-killing of 77 people in Norway in 2011 had been partially plotted within the popular first-person shooter Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare (2007). In fact, within days of writing this introduction, a British man has even been arrested for an act of ‘swatting’, a reckless prank whereby players of online games trace the IP address of their competitors, calling in terrorist hoaxes to local police stations that usually result in the disruption of gameplay by a very real, and very well armed S.W.A.T. Team. In this instance, the unwitting victim was shot.

So how does all of this all bring us back to the book I’m introducing you to? Well, it suggests that ‘game space’ has very real overlaps with lived space. My examples are all admittedly alarmist, (almost comedically so) but they illustrate in a necessarily visceral way the peculiar osmosis occurring between the activities of game communities and the worlds beyond the polygonal membranes we always assumed would contain them. As a result, it seems more timely than ever to explore the emergent discursive spaces of online games, which is what this little book seems to do with great perception, speculation, patience and wit. It’s a space defined by its permissiveness, user entitlement and the frequently voidal nature of free time. A space we’d do well to consider a legitimate but fractious channel of communication between polarised parties.

If you’re unfamiliar with Crowe’s previous work, then it might be helpful to know that this project encapsulates pretty much all of the longstanding hallmarks of his practice to date: slander, Californian catastrophe, artistic infringement into communities that have no prior knowledge of his work, and the comedic potentiality of bespoke virtual worlds. He pretty much anticipated the violent community he’d be engaging with this book in a short piece for one of his previous pamphlets, The Organ Grinder, which begins:

Huge muscle men.

Everywhere.

All screaming at each other.

Something about gym equipment.

Some are barking.

Screeching, barking, rabid.

Basically gearing up to kill each other.

A huge percentage of game space still has major problems with ‘non-normative’ subjects and behaviours. It has problems with gender, race, and sexuality: all identities that came to the fore as targets for the terroristic actions of trolls through the period we now refer to as ‘gamergate’, a supposed reaction to ‘ethics in games journalism’ that was, in truth, the forceful preservation of exclusive community codes that sought to keep ‘others’ out of an apparently now rarified white patriarchal space. Journalists and media theorists are keen to draw direct links between gamergate and the formation of the alt-right. Indeed, arch-troll Milo Yiannapolous himself designated gamers a core component of the new conservatism in his now canonical text An Establishment Conservative’s Guide To The Alt-Right (2016).

Crowe doesn’t engage the world of GTA Online in a conspiratorial, diagnostic, overtly political sense, but in a broader, more tolerant, less paranoid way, and with a good dose of humour, surely the optimal tool for combatting aggression. If anything, his Attempt… outlines a methodology that seems more than valuable right now, patiently noting the forms of behaviour and dialogue that seem to exemplify the kinds of permissiveness, brashness, and nihilistic provocation that also undergird the social movements contiguous with the demographics he’s encountering in game, the ‘beta uprising’ and the ‘manosphere’ for example.

Whilst we might understand Oulipo author Georges Perec’s original Attempt… as a playful form of critical pedestrianism glimpsed in part through the antiquated lens of the flaneur or ‘man of the crowd’, a figure whose aimless and unhurried perambulations affords him (and it has nearly always been a ‘him’) a novel view of the city, Crowe’s observations of San Andreas can’t really be read in the same way. The flaneur’s ‘unique’ vision was borne of a certain prestige, of the luxury of leisure time that provided a mode of separation from the bustle of the city, a vantage point from which the furore of urban chaos could be bemusedly pondered. The flaneur’s privileged view was always protected by his social, economic and sexual identity. For Crowe, immersed in a fictional world whose texture-mapped fabric is saturated with irreverence, such attempts at dispassionate observation are impermissible. In an online game one can’t simply sit things out. In fact, indifference, inertia or reluctance to play are seen as an absurd breach of rules punishable by sticky bomb, or, ideally, a 360 no scope headshot.

This had fantastically illustrative consequences when, in attempting to look the part whilst preparing to spend prolonged periods on a Los Santos street corner, Crowe guided his avatar into a gentleman’s outfitters in order to try on a series of suitably Parisian turtle neck sweatshirts. Caught in the act of trying to replicate the look of Perec himself, he was approached by another player who proceeded to casually stab him in the neck. His silly artistic project obviously has no currency within the hardline meritocracy of GTA Online, the only valid forms of participation being those that replicate the predetermined accolades of good driving, good shooting, or noxious tricksterism. In this sense, his Attempt… sits neatly alongside recent work by artists such as Angela Washko, whose Council on Gender Sensitivity and Behavioural Awareness in World of Warcraft (2013 - ) pointedly confronts gamers with their thoughts on the term ‘feminism’, or the provocations of youtube prankster danielfromsl (Daniel From Second Life) whose frustratingly non-compliant behaviour teases out the social anxieties and identitarian prejudices that underscore a lot of online play.

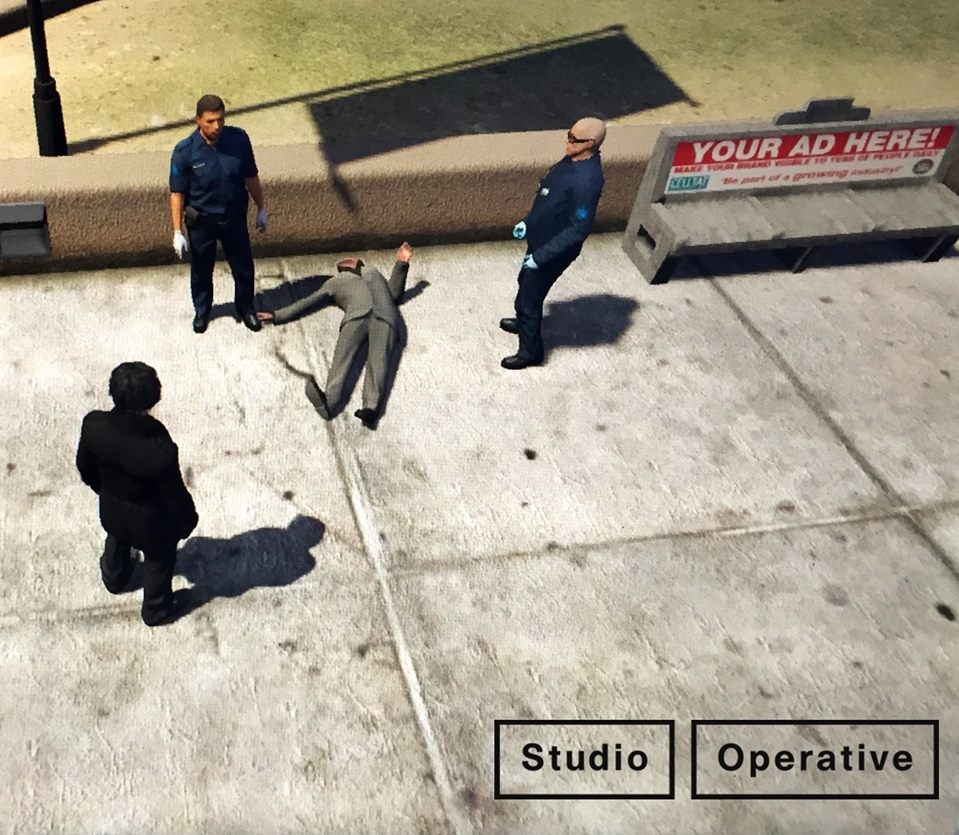

In paying attention to this world Crowe’s done a timely, necessary, elucidating and funny thing. I’m jealous and frustrated that he got there first. Jealous of the book’s inventiveness, inquisitiveness and relentless mirth. It’s a book that only he could’ve written and for that I’m thankful. But in the spirit of GTA Online’s oneupmanship, I’ll close with this. If you do happen to see the artist online, roving the streets of Los Santos, please do kill him. And as he lies there, bleeding out onto the sunbathed sidewalk, uttering his final breaths before a re-spawn, be sure to tell him I sent you.