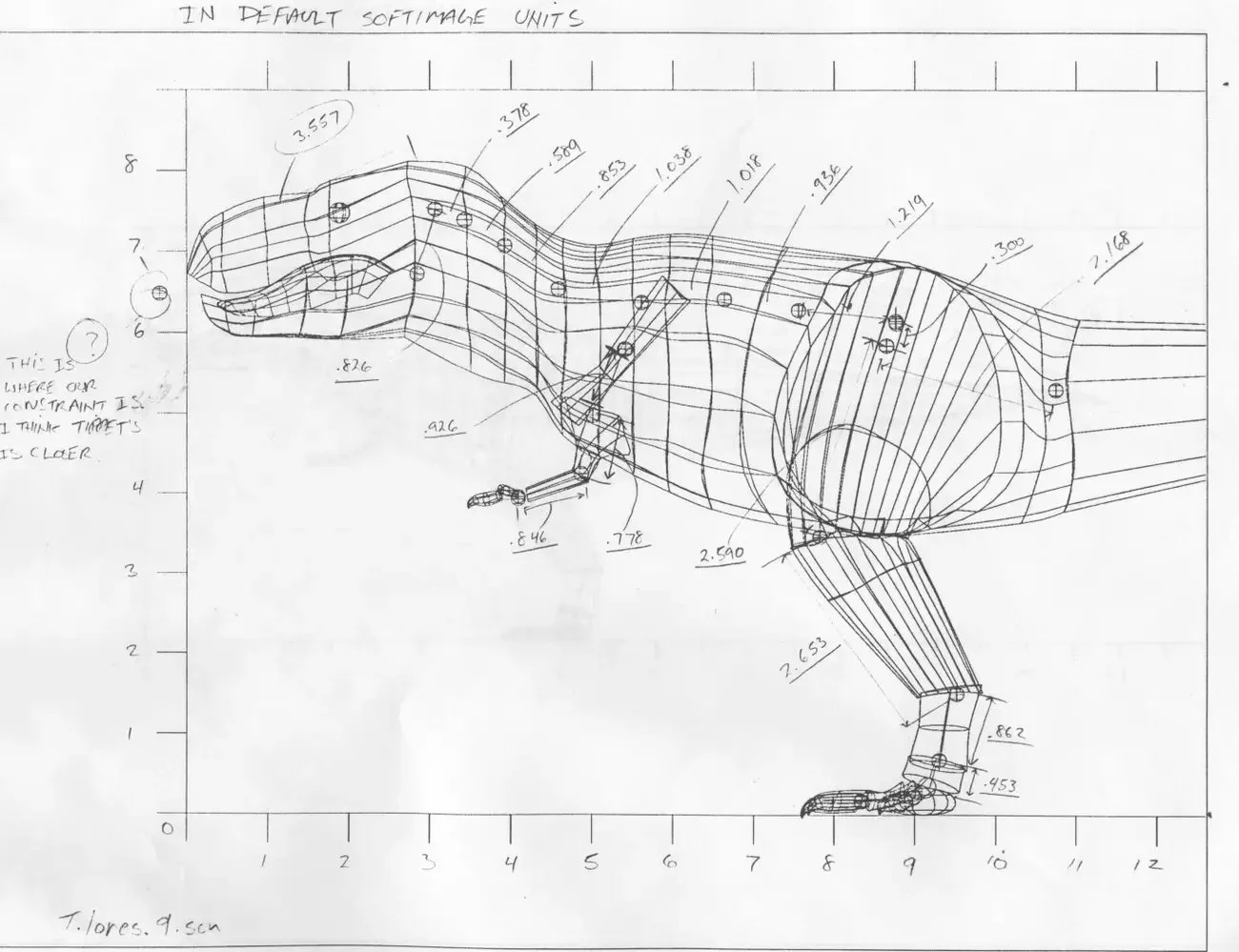

Analogue prototyping for Jurassic Park’s CGI, Steve Williams, 1991

ESSAY

Mutant Media

First published by Art Review, September 2023

In his farsighted 2003 essay ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Biocybernetic Reproduction’, US academic W.J.T. Mitchell donned a critical hazmat suit to dissect a newly intrusive dynamic of capitalist extraction. Like Walter Benjamin’s 1935 essay, upon which its title fondly riffed, Mitchell’s text questioned ideas of ‘aura’ and ‘reproducibility’ but crucially redirected them towards a moment in which the codes of biological matter had been cracked, replicated and financialised. Here, reproduction was no longer tethered to representation but corporeally entwined with the reconstitution of living matter through techniques of genome sequencing, tissue cloning and gene editing. Given the lab-bound, cellular scale of these innovations, Mitchell wondered, how might the molecular evolutions of genomic capital be communicated in the public domain? What’s more, how could a work of art find discursive purchase in an age characterised by the very mutability of life, where each modified cell might itself be considered a living work of art?

Despite his spirited prognoses, Mitchell’s proposed examples were deader than dodos: cloyingly humanist works by Damien Hirst and Antony Gormley provided inert symbols of the human as an environmentally conditioned subject, but they did little to capture the vertiginous spirit of recombinant genetic data. Beyond the remit of studio-art practice however, Mitchell did sense the stirrings of a vital correlate for the biocybernetic era within the animated fantasies of popular culture. It’s one that we might, with hindsight, suggest illustrated a more fundamentally (and perhaps unsettlingly) productive relationship between life and image than any static assemblage of vitrines, pills or generously endowed body casts.

From the retro-engineered dinosaurs of Steven Spielberg’s Jurassic Park (1993) to the cybernetics of Kon Satoshi’s anime Paprika (2006), from the plasmatic pliability of Nickelodeon’s anarchic cartoon Ren & Stimpy (1991–96) to the genetic deviances of Shinji Mikami’s videogame Resident Evil (1996), a pop-cultural index of the biocybernetic imaginary was being metabolised in the decades flanking the millennium. These were novel forms of animation in which biological matter was recharacterised by the exhilarating metastases of mutation.

More importantly however, these animated imaginings betrayed the shared toolsets of commercial animation and the genetic sciences, both of which employed the interrelated media of analogue drawing and digital code as fundamental building blocks of their industries. As Erica Borg and Amedeo Policante suggest in their recent book Mutant Ecologies: Manufacturing Life in the Age of Genomic Capital (2022), highlighting this affinity in a way that describes the animator’s studio as the geneticist’s lab, ‘mutant forms of life were planned in the abstract, their genome designed on paper, and tentatively realised in practice’.

This entanglement of life and image in a techno-political scenario characterised by the ubiquity of animation – from graphically rendered feature-films and the animated interfaces of health-tracking apps, to motion capture, augmented-reality videogames and genetic-data simulation – has been beautifully conceptualised by media theorist Deborah Levitt as the ‘animatic apparatus’. For Levitt, the dual senses of ‘animation’ as both the production of life’s representation and the very condition of ‘aliveness’ have converged at a protean life–screen nexus in which ‘life becomes not a property that one has, or doesn’t, but a site for intervention, production, poiesis’. Like a conceptual canker sprouting from Mitchell’s essay, the animatic apparatus situates animation and vitality along the same co- constitutive continuum: while life is increasingly produced and conditioned by images, images are progressively positioned to call new life into being.

The animatic apparatus provides a neat cipher to Genetic Automata, a series of four striking essay-films by British artists Larry Achiampong and David Blandy currently on display at London’s Wellcome Collection that map the interrelation of bodily matter with digital interfaces, troubling lineages of racial representation and the dynamics of computational power. The exhibition echoes the Wellcome’s own displays by distributing its artworks among idiosyncratic museological exhibits, grouping ephemera from the uncomfortable histories of scientific racism alongside fragments of speculative culture, including Afrofuturist comic books by Nnedi Okorafor, Hideo Kojima’s cultic riff on weaponised cloning, Metal Gear Solid (1998), and even that infamously hollow clarion-call for racial equity, the ‘morphing’ sequence from Michael Jackson’s 1991 music video Black or White. In one vitrine, late-nineteenth-century photographic studies of Jewish children created by eugenic fabulist Francis Galton are layered to demonstrate supposed racial differences in a manner not too dissimilar from the multiplanar cel-animation techniques developed by Walt Disney.

Achiampong and Blandy’s films are calmly provocative, questioning the assumed authority and unacknowledged biases of scientific speculation and its pop-cultural residues. A Terrible Fiction (2019) recounts the unacknowledged importance of John Edmonstone, an enslaved Black man who taught Charles Darwin the art of taxidermy, while simultaneously exploring the discriminations of evolutionary biology, the deceptions of popular genetic ancestry tests and the foundational genocide that gave rise to modern Homo sapiens, while A Lament for Power (2020) reanimates the voice of Henrietta Lacks, an African-American woman whose cancer cells were posthumously subject to cultivation and testing by the biomedical industries without her consent due to their remarkable propensity for self-replication. The film hauntingly evokes the cellular afterlives of Lacks alongside footage from the controversial videogame Resident Evil 5 (2009), in which a bioterrorism incident casts African victims as undead adversaries caught in terminal gameplay loops.

While foregrounding the ongoing traumas of ‘race science’ and epidermal prejudice through narration that is, by turns, accusatory and wearied, Achiampong and Blandy never fail to intuit unifying possibilities in pop culture’s shared spaces, rallying dialogue from cult media to suggest opportunities for historical revision and communal understanding. “Can’t we shapeshift too, work together to undermine these fantasies?” the artists ask via pointed narration in the concluding film of the series, _GOD_MODE_ (2023), figuring racial capitalism as a game that might be rebooted, a fiction that could be rewritten by a newly generated character. Might a new operating system be assembled from the resources the artists draw upon, Genetic Automata seems to suggest, one that exploits the animatic possibilities of protean identities forged from more equitable sciences and entertainments? Perhaps this mutant media is the latent postscript to Mitchell’s essay, its distressing oversights and liberating possibilities the messy inheritance of a biocybernetic age within which we’re still working to orientate ourselves? Following Levitt, we could suggest that we’ve never been at a more critically intimate vantage point from which to assess animation’s enduring appeal.